A dean at an Australian university sought to correct some of his papers. He received a retraction instead.

We wrote last year about Marcel Dinger, dean of science at the University of Sydney, who was a coauthor on five papers with multiple references that had been retracted. In May 2024, Alexander Magazinov, a scientific sleuth and software engineer based in Kazakhstan, had flagged the papers on PubPeer for “references of questionable reliability.” Magazinov credited the Problematic Paper Screener with helping him find them.

Dinger told us at the time he intended to work with editors to determine whether the five papers should be corrected or retracted.

This May, one of the papers, published in 2021 in The Journal of Drug Targeting, was retracted – with a statement that the authors didn’t agree with the decision. The article has been cited 14 times, according to Clarivate’s Web of Science.

We followed up with Dinger, who told us he and his coauthors had reached out to the journal with a correction note. “As the conclusions of the paper were not impacted by the retracted citations, the authors felt that a corrigendum was an appropriate measure to uphold the integrity of the scholarly record,” Dinger said.

This correction note coincided with the editorial team and publisher’s investigation, which a Taylor & Francis spokesperson told us “was prompted by concerns, raised initially by third parties and subsequently by one of the authors, regarding references cited in the review article which had later been retracted.”

The investigation “identified enough concern about the relevance and accuracy of other references that we and the Editorial Team no longer had confidence in the content presented and concluded that a retraction was required,” the spokesperson said.

But Dinger told us “the journal did not supply the authors with any specific information regarding the remaining concern on the ‘relevance and accuracy of some other references’ cited in the publication, so we were unable to assess the Editorial Team and Publisher’s basis for retraction.”

One of the other flagged papers received a lengthy correction in December, which the authors agreed with. Dinger told us he “contacted the associated journals in June last year with corrigendums,” but the other three papers remain unmarked.

Mohammad Taheri, a coauthor on all five of the papers, said in an interview he also disagreed with the retraction because “there [were] no irrelevant citation[s].” Taheri has nearly 100 papers with comments on PubPeer. He has responded to many of these comments, including on the recent retraction.

Dinger declined to comment when asked about his collaboration with Taheri and if he knew about the large number of his papers on PubPeer. He coauthored 15 papers with him from 2020 to 2022 but has not published with him since.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at team@retractionwatch.com.

Dear RW readers, can you spare $25?

The week at Retraction Watch featured:

- Viral paper on black plastic kitchen utensils earns second correction

- Harvard researcher’s work faces scrutiny after $39 million private equity deal

- When it comes to conflicts of interest, affiliations are apparently no smoking gun

- Do you need informed consent to study public posts on social media?

- Retraction for ‘unsound’ analysis was ‘disproportionate and discouraging,’ author says

Our list of retracted or withdrawn COVID-19 papers is up past 500. There are more than 60,000 retractions in The Retraction Watch Database — which is now part of Crossref. The Retraction Watch Hijacked Journal Checker now contains more than 300 titles. And have you seen our leaderboard of authors with the most retractions lately — or our list of top 10 most highly cited retracted papers? What about The Retraction Watch Mass Resignations List?

Here’s what was happening elsewhere (some of these items may be paywalled, metered access, or require free registration to read):

- “How the Growth of Chinese Research Is Bringing Western Publishing to Breaking Point.”

- “NIH Plans to Cap Publisher Fees, Dilute ‘Scientific Elite.'”

- “Research-integrity sleuths say their work is being ‘twisted’ to undermine science.”

- “Nature retracts paper on novel brain cell type against authors’ wishes.”

- Limiting federal scientists to government journals “would compromise scientific research:” op-ed.

- “Most science is published from countries lacking in democracy and freedom of press,” say John Ioannidis and a colleague.

- “Can academics use AI to write journal papers? What the guidelines say.”

- “The world of scientific journals on the verge of suffocation.”

- A study linking wildfire smoke and dementia risk is retracted after researchers find an “and/or” coding error.

- Minister of Education nominee “faces allegations of thesis theft” and “splitting papers” before confirmation hearing.

- Researchers find “patterns of irreproducibility across an entire life sciences research field” after analyzing 400 Drosophila papers.

- Committee finds “gross negligence” in work by former German university president.

- “Tell the Bot to Tell the Bot About the Bot”: When AI instructions show up in academic papers.

- “To bioRxiv or not to bioRxiv?” Commentary on a study of “How COVID-19 affected academic publishing.”

- Editorial: “Addressing gaps in author and reviewer gender diversity.”

- “Scholarly publishing’s hidden diversity: How exclusive databases sustain the oligopoly of academic publishers.”

- University “cuts funding, class credit status from undergraduate research journal.”

- Psychology’s research problems lie beyond its practices in its fundamentals, which are “grounded in their insufficiently elaborated underlying philosophy of science“: researchers.

- Survey reveals over a quarter of researchers report observed misconduct “within their networks,” but less than 3% tell on themselves.

- “The Race to Publish, Publication Pressures, and Questionable Practices: Rethinking the System.”

- The 13 top Indonesian universities flagged in the research integrity risk index.

- A proposal for dual journal submission which works “by requiring the researcher to give the right to proceed to peer review (and eventual publication) to only one journal.”

- “Strengthening Australia’s research integrity system“: More on Charles Piller’s book.

- “Metascience can improve science — but it must be useful to society, too.”

- COPE’s new guideline on guest editors. A look at our recent coverage of a guest editor blunder.

- “Bias in STEM publishing still punishes women”: An adapted excerpt from a physician researcher’s book.

- Systematic reviewers are “uniquely positioned – and ethically obligated – to detect problematic studies and champion research integrity.”

- “Bounty Hunters for Science”: a proposal for funders to “establish one or more bounty programs aimed at rewarding people who identify significant problems with federally-funded research.”

- “Japan requires name change after marriage — with big effects on female scientists.”

- Researcher says authors should “reproduce an existing paper in the same field that is currently under review” for every paper they submit to be published.

- “AI ‘scientists’ joined these research teams: here’s what happened.”

- “Leadership change at African journal sparks calls for bold reform,” and “researchers say it must evolve to better serve the scientific community.”

- “Staying ahead of the curve: a decade of preprints in biology.”

Retraction Watch Journalism Internship

Applications for our fall journalism internship are open! We typically take current or recent journalism graduate students with an interest in research integrity and scientific publishing. Learn more and apply here. Deadline: July 18.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at team@retractionwatch.com.

What's up, podcast listeners? We've got another episode of our podcast They Call Us Bruce. (Almost) each week, my good friend, writer/columnist Jeff Yang and I host an unfiltered conversation about what's happening in Asian America, with a strong focus on media, entertainment and popular culture.

In this episode, we welcome Maggie Kang, creator and co-director of the hit Netflix animated feature Kpop Demon Hunters. She talks about the seven-year journey of bringing the film to life; behind-the-scenes insights on crafting an epic animated action musical that incorporates both supernatural demon lore and kpop idol culture; assembling the voice and music team to tell this uniquely Korean story; and the incredible, unexpected global response to the movie. Also: The Good, The Bad, and The WTF of making Kpop Demon Hunters.

Read more »

The editors of Scientific Reports have retracted an article on burnout because the statistical analysis of its main finding was “unsound.” But the authors dispute the editors’ take on the statistics and claim a mistake in the paper triggered an unfair review.

For the paper, published in November, the authors measured concentrations of cortisol in hair samples from nearly 500 healthcare workers in Buenos Aires to study the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on chronic stress and burnout. The analysis hinged on a statistical method called mediation analysis.

“Mediation analysis is a method to understand how one thing causes another by looking at what happens in between,” said lead author Federico Fortuna, of the Institute of Physiopathology and Clinical Biochemistry at the University of Buenos Aires. “In our study, we examined whether depersonalisation mediates the relationship between hair cortisol — a biological stress marker — and emotional exhaustion, a key psychological symptom of burnout.”

On the day the paper was published, Ian Walker, an environmental psychologist at Swansea University in Wales, saw the article and noticed something amiss. He posted on Bluesky, “How did editor and reviewers not spot that the (wrongly labelled) mediation statistic sits outside its own confidence interval?” His post included a screenshot from the paper showing the issue.

That was in fact a typographical error, Fortuna conceded. “Neither the reviewers nor we noticed the typo during the peer review process — and yet we all missed it,” he said. What was labeled as the indirect effect should have been the direct effect, and the confidence interval was missing a zero.

The editors at Scientific Reports saw Walker’s Bluesky post and sought clarification from the authors, according to correspondence seen by Retraction Watch. But then a few weeks later, the journal followed up, stating, “We sought advice from our Editorial Board on your article and I’m afraid some further concerns have now been identified.”

What followed was a lengthy back-and-forth, and, ultimately, the paper’s retraction on May 19. The notice reads:

Post-publication peer-review has confirmed that the basis of the mediation analysis itself is unsound. Hair cortisol concentration, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalisation are all indicators of stress and as such investigating causal effects between these is not justified.

The notice continued with some specific details, and concluded: “The Editors no longer have confidence in the claims of this Article.”

But Fortuna said while the way his group presented the stat in question had an error in it, the editors misinterpreted the analysis. “It is widely recognised in the field of mediation analysis that a statistically significant relationship between the independent variable and the mediator is not a strict requirement,” he said. “The non-significant correlation reported [in the study] between hair cortisol and depersonalisation does not invalidate the overall mediation model, particularly given that the indirect effect remained statistically robust.”

Elizabeth Mann, deputy editor of Scientific Reports, declined to comment on the article’s review process.

“It seems the retraction was driven by confusion over statistical methods rather than any actual flaw in the analysis — and it’s concerning that this confusion is coming from the editorial side, not the peer reviewers who originally approved the work,” Fortuna told us.

In a follow-up email, Walker, whose Bluesky post set off the review, said his post was a comment “on an error in statistical reporting that I thought spoke to issues with the peer review process in general.”

Fortuna emphasized that “the only actual error in the paper was a simple typographical oversight — a missing zero in the confidence interval for the direct effect,” he said. “We promptly acknowledged this and submitted the corrected values. Instead of addressing this as a standard corrigendum, the journal opted for a full retraction, citing methodological unsoundness that, in our view, was not present.”

“We stand by the validity of our methods and results,” Fortuna said. “The decision to retract — based on a misunderstanding and a minor formatting error — feels disproportionate and discouraging.”

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at team@retractionwatch.com.

Squid Game is back! The third and final season of the worldwide phenomenon has dropped, and I'm pleased to share that I'm back as host of Squid Game: The Official Podcast, from Netflix and Mash-Up Americans. Join me and co-host Kiera Please as we suit up and break down every shocking twist and betrayal, and the choices that will determine who, if anyone, makes it out alive. Alongside creators, cultural critics, and viral internet voices, we'll provide our own theories for how the season ends, and what Squid Game ultimately reveals about power, sacrifice, and the systems that shape us.

Spoiler alert! Make sure you watch Squid Game Season 3 before listening on.

For our final bonus episode Kiera and I head to New York City for an exclusive sit-down with the minds and hearts behind Squid Game, series creator and director Hwang Dong-hyuk, the unforgettable Player 456 himself, Lee Jung-jae, and the enigmatic Front Man, Lee Byung-hun. The masks are off! We do a deep dive with some burning questions about the show's most iconic moments and characters, and get real with the legends behind the global phenomenon.

Read more »

The retraction of a paper looking at posts in a Reddit subforum about mental illness has once again raised questions about informed consent in research using public data.

To study the experience of receiving a diagnosis of schizophrenia, a U.K.-based team of researchers collected posts from the Reddit subforum r/schizophrenia, which is dedicated to discussing the disorder. They analyzed and anonymized the data, and published their findings in June 2024 in Current Psychology, a Springer Nature journal.

The paper prompted backlash on X in the subsequent months, and in the Reddit community used for the study. People on the subreddit were concerned about the lack of consent, potential lack of anonymity, and the hypocrisy of discussing ethics in the paper while not seeking consent, a moderator of that subreddit who goes by the handle Empty_Insight told Retraction Watch.

“The subreddit has a clear rule that all research requires approval of the moderators, which was affirmed to be sufficient by the community after the fact,” Empty_Insight, who coordinates all research conducted on the subreddit, told us. “However, no such attempt at contact was made.”

“It is no small feat for someone with schizophrenia who grapples with paranoia to speak in a semi-anonymous setting, so the intrusion is particularly violating in light of that,” the moderator added. They also said this intrusion feeds historical mistrust of researchers due to “the not-so-distant past of unsavory, unethical practices where consent was foregone and the only reason that could be given was ‘The ends justify the means’.”

Researchers have long debated the ethics around informed consent when using public data. In 2016 the Center for Open Science took down a dataset of users of the dating site OkCupid from its Open Science Framework because it contained potentially identifying information on people who did not consent to its use. Earlier this year, we reported on researchers who posted AI-generated messages on a Reddit subforum without the forum’s, or user’s, knowledge.

Following “extensive complaints, feedback, and discussions within the team, other researchers, and people with lived experiences,” the researchers chose to retract the paper, the December retraction notice stated.

“We are sorry that our work caused distress to the community in question and consequently retracted the paper,” said lead author Minna Lyons, a lecturer at Liverpool John Moores University in England.

Although the researchers stated in the paper that they “secured ethical approval,” relatively few study authors who use data from Reddit seek approval from a research ethics committee. A 2021 study found only 13.9% of studies examined mentioned a related term like “institutional review board.”

Many papers have discussed the ethics of using social media, and Reddit in particular, in research. Groups such as the Association of Internet Researchers have published ethical guidelines that detail the difficulties in obtaining informed consent and urge researchers to mitigate harm by considering the questions they use in their research, how they process sensitive data, and how they deal with risk during data storage, aggregation, and publication.

“This an important emerging area where the researchers using pervasive data and internet technologies are giving more thought to how ethical standards should be applied, and we commend the authors for taking the proactive step to retract their paper given the concerns around consent,” Ellie Gendle, head of journals policy at Springer Nature, told Retraction Watch in an email. Due to “challenges in forming a universal policy” and a lack of ”consistently held standards” on the use of these types of data and technologies, the journal evaluates each paper on a case-by-case basis, she told us.

After learning about the Current Psychology paper, the subreddit moderators conducted a poll of its users on how to address future research requests. They chose to stick to the existing research approval policy, and added a user flair – a tag that appears next to a user’s handle – to opt out of data collection for research purposes. Empty_Insight noted that people didn’t use this flair, so they have since removed it.

The decision to retract the paper “sets the right precedent, and sends the signal that what degree of privacy can be preserved for those with psychotic disorders will be respected,” Empty_Insight said. “We cannot forgo consent for the sake of convenience.”

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at team@retractionwatch.com.

Seven papers on various aspects of vaping and cigarettes published in Toxicology Reports listed each authors’ affiliation – the tobacco company Philip Morris International – when they originally appeared in the journal between 2019 and 2023. And all but one article disclosed the funding for the research originated from the company.

That apparently wasn’t enough for the journal.

Toxicology Reports has issued a correction to add those affiliations as a conflict of interest. The statements were “missing or incorrect” in the original papers, according to the correction notice, published in the June 2025 issue of Toxicology Reports. In addition to reiterating that the authors work for PMI, the correction also adds to the conflict of interest statements that the authors were funded by the company and used its products in the research.

“While the authors’ affiliation to Philip Morris was indeed listed on the articles, Elsevier policies and ICMJE recommendations require disclosures of competing interests to be added to articles, and full details on the potential conflict of interests of authors, where applicable, must be provided,” a spokesperson for Elsevier, which publishes the journal, told us.

The spokesperson said the issue “was flagged to us recently” but would not say by whom.

Elsevier contacted the authors at Philip Morris, and both parties agreed to the correction. “At the publisher’s request, we added details to the conflict of interest section to reflect information already included in the author affiliations,” a spokesperson for the company said.

The correction added the following “Declaration of competing interest” to each paper:

The work reported in this publication involved products developed by Philip Morris Products S.A., which is the sole source of funding and sponsor of this research. All authors are employees of PMI R&D or worked for PMI R&D under contractual agreements.

The papers included reviews and primary research on the toxicology of heated tobacco and e-cigarettes. Others ranged from a study of aerosols from hookah tobacco to a methods paper comparing multiple cigarettes for use as a baseline reference in studies of other tobacco products. Most of the papers have been cited up to 19 times; one of them has been cited 63 times, according to Clarivate’s Web of Science.

Toxicology Reports has had oversight issues in the past. In 2021, the journal issued an expression of concern on an entire special issue on COVID-19 over “concerns raised regarding the validity and scientific soundness of the content.” At least two of the papers in the issue have since been retracted.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at team@retractionwatch.com.

Squid Game is back! The third and final season of the worldwide phenomenon has dropped, and I'm pleased to share that I'm back as host of Squid Game: The Official Podcast, from Netflix and Mash-Up Americans. Join me and co-host Kiera Please as we suit up and break down every shocking twist and betrayal, and the choices that will determine who, if anyone, makes it out alive. Alongside creators, cultural critics, and viral internet voices, we'll provide our own theories for how the season ends, and what Squid Game ultimately reveals about power, sacrifice, and the systems that shape us.

Spoiler alert! Make sure you watch Squid Game Season 3 Episode 6 before listening on.

The Game ends here. In the gripping series finale, "Humans Are..." Kiera and I sit with the full emotional weight of the series' conclusion -- unpacking Player 456's remarkable final act of defiance, the Front Man's quiet reckoning, and the question at the heart of the show: what does it mean to be human in an inhumane world? We revisit lingering fan theories, reflect on the characters we’ll never forget, and explore a final twist that raises even more questions than it answers.

Read more »

Just as a Harvard lab brought in tens of millions of dollars in private equity funding to pursue new treatments for obesity, past research from its lead investigator has come under fresh scrutiny.

Last month, the lab of Gökhan Hotamışlıgil, a professor of genetics and metabolism at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, secured a $39 million dollar investment from İş Private Equity, an Istanbul-based firm. The partnership centers on FABP4, a protein associated with obesity and other metabolic conditions.

But over the past decades, two of Hotamışlıgil’s papers have been corrected for image duplications, and since the announcement, renewed scrutiny of Hotamışlıgil’s work appeared on PubPeer, including for issues with statistical analyses.

“Of course when we become aware of an irregularity or mistake, or someone makes an allegation, we take these issues very seriously and do all we can to address the question,” Hotamışlıgil told us in an email.

The most recent comments are from Reese Richardson, a computational biologist who looks into scientific reproducibility. Richardson said he became curious about Hotamışlıgil’s work after seeing news about the funding deal. He soon found existing concerns flagged on PubPeer.

“I figured that it would be worthwhile to check his papers out,” Richardson told us. Initially, two articles piqued his interest, although Hotamışlıgil is not the senior author on either.

In one PubPeer post, Richardson raised concerns about a 2017 paper in Nature Medicine in which he discovered mislabelling of data, claims of statistical significance the raw data didn’t seem to support, and some missing source data. The author contribution statement indicates Hotamışlıgil oversaw some of the experiments.

Richardson also looked into a 2019 article in Cell Metabolism that contained “either wrongly reported or apparently manipulated” statistics, he told us. Nearly every result “features inexplicable methodological inconsistencies or reporting errors,” he wrote on PubPeer. “These result in a massive exaggeration of the effects observed.”

According to Richardson’s analysis, some statements made in the paper were true only when samples were arbitrarily excluded, but the methods didn’t describe any procedure for the exclusion of samples. According to the author contribution statement, Hotamışlıgil helped with the discussion and interpretation of results.

James Heathers, a scientific sleuth and director of the Medical Evidence Project — an initiative of the Center for Scientific Integrity, the parent nonprofit of Retraction Watch — said the extent of the problem is mostly unknowable. “How can you adjust for the effects of data that isn’t presented?” If outliers are left in the dataset, but redacted from the analysis, “the redaction should be explained in 100% of cases,” he said.

Hotamışlıgil said the work for those two papers was led by Yu-Hua Tseng, another researcher at Harvard, and his group’s involvement was limited. “We have provided some help with their experiments, my fellow Alex Bartelt provided some training and physiology and biochemistry experiments,” he told us. “We were not directly involved with the rest of the paper.”

Apart from Richardson’s recent comments, anonymous commenters on PubPeer have pointed out irregularities in Hotamışlıgil’s published work over the years. A 2008 PLOS One paper, for example, was corrected after a commenter found a duplicated image. A similar issue was flagged in a 2020 paper in Cell Metabolism, which included two identical images in one figure. “We deeply regret this unfortunate error,” one of the authors wrote on PubPeer. That paper was also corrected. Another flagged paper appears to contain similar-looking blots. Hotamışlıgil is listed as the senior and corresponding author on each of these papers.

For a 2019 article in Science Translational Medicine related to FABP4 — the protein at the center of the new funding deal — an anonymous commenter questioned the statistical significance of the findings. After analysing the raw data, the commenter found no statistical significance for some findings reported in the paper, despite them having been reported as such. Hotamışlıgil was the senior and corresponding author for this paper. Heathers said these statistical concerns comprised “a concerning pattern of oversights” and would “necessitate exactly the kind of audit that universities tend not to do.”

Reflecting on the PubPeer posts appearing under his name, Hotamışlıgil said, “In many cases, there is no basis, for example there are several posts where there is no comment, there is even one post about a review that I have written but nothing can be found at the post, and some state opinions or perceptions.”

Hotamışlıgil also co-authored a 2002 Nature paper with Michael Karin, a prominent cancer researcher and the subject of previous scrutiny for image problems, including in our own reporting. The paper was corrected in 2023 after PubPeer commenters identified duplicated blots. In the correction, the editors wrote: “as the raw data for the blots used in the manuscript are no longer available, unfortunately we cannot ascertain the issue with the figure.” Hotamışlıgil was listed as the senior and corresponding author on this paper.

He has also co-authored papers with Umut Ozcan, who in 2015 was accused by postdocs of fabricating data and creating a hostile work environment. The case was dismissed from court in 2018. Hotamışlıgil was Ozcan’s graduate advisor, and the two articles where Hotamışlıgil is listed as the senior and corresponding author, and Ozcan as the first, appear to contain duplicate lanes in the blot data or have a mismatched number of lanes. Mike Rossner, an image manipulation consultant, said these PubPeer allegations also had merit, although the mismatched lanes could be a clerical error, which is “unusual, but not unheard of,” he added.

Harvard has described the Turkish firm’s partnership with Hotamışlıgil’s lab as a “potential model” for revenue for the T.H. Chan School. According to a press release about the funding, the school has seen almost $200 million in federal funding dry up in recent months, and the Trump administration terminated nearly every direct federal grant for research and training. The deal was in progress before the administration came into office, and would have taken place despite the recent decline in federal funding, a Harvard spokesperson told us.

Iş Private Equity is currently the only private equity funder at the T.H. Chan School, although the school is “accelerating” efforts to engage with the private sector, the spokesperson said.

Such arrangements between universities and private equity are “not common,” Robert Field, a professor of law and public health at Drexel University in Philadelphia, told us. In recent years, private equity has been moving into health care — buying up hospitals, nursing homes and physician practices — but investing into universities is unusual. Private equity is “by nature, profit oriented, and usually short-term profit oriented,” Field said, and are most likely to fund projects that are close to fruition, he said.

The research has the same oversight, regardless of the funding source, said the Harvard spokesperson, and they will not accept collaboration that “imposes any restriction on our faculty’s freedom to publish and speak about their research.”

Richardson told us he shifted his focus to Tseng, who was the senior author on the two recently flagged papers. Richardson came across a different pair of 20-year-old papers she was the lead author on, both of which seem to contain similarities between parts of Western blots, or inconsistent features in the blot lanes.

Rossner told us the allegations about image duplications had merit and the data raise enough concerns for a journal editor to want to verify the published results. Some of the PubPeer comments note mismatched lanes in the Western blots; this could be due to clerical error, Rossner said, and one image was too low resolution to tell whether it could be a duplicate.

Richardson has also since raised concerns about several other papers by Tseng, citing statistical irregularities.

Tseng told us she is aware of the comments and has “already discussed them with the leading authors.” Since speaking with Retraction Watch, she has responded on the platform, writing, “Thank you for your comments. We are currently reviewing the original data and conducting additional analysis. We will respond to the comments once the investigation is complete.”

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at team@retractionwatch.com.

The authors of a paper that went viral with attention-grabbing headlines urging people to throw out their black plastic kitchen tools have corrected the work for a second time.

But a letter accompanying the correction suggests the latest update still fails “to completely correct the math and methodological errors present in the study,” according to Mark Jones, an industrial chemist and consultant who has been following the case. “The errors are sufficient to warrant a restating of the abstract, sections of the paper and conclusions, if not a retraction.”

The paper, “From e-waste to living space: Flame retardants contaminating household items add to concern about plastic recycling,” originally appeared in Chemosphere in September. The study authors, from the advocacy group Toxic-Free Future and the Amsterdam Institute for Life and Environment at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, looked for the presence of flame retardants in certain household plastic items, including toys, food service trays and kitchen utensils.

The researchers found toxic flame retardants in several items that wouldn’t ordinarily need fire protection, such as sushi trays, vegetable peelers, slotted spoons and pasta servers. Those items, the authors suggested, could have been made from recycled electronics — which do contain flame retardants.

Then, for kitchen utensils, the authors used findings from another study, which measured how toxic chemicals including BDE-209 transfer from black plastic utensils into hot cooking oil, to estimate potential intake based on findings in their own study. They estimated a daily intake of 34,700 ng/day of BDE-209 from using contaminated utensils, which “would approach the U.S. BDE-209 reference dose” set by the Environmental Protection Agency, they reported.

But the authors miscalculated that reference dose. They had put it at 42,000 ng/day instead of 420,000 ng/day. That hiccup led to the first correction to the paper, published in December. “This calculation error does not affect the overall conclusion of the paper,” the authors said in the corrigendum.

The latest corrigendum, published July 3, states the formula the authors used to estimate exposure to the flame retardant BDE-209 “was misinterpreted.” It continues:

This misinterpretation led to an overestimation of the BDE-209 exposure concentration. The corrected estimated BDE-209 exposure is 7900 ng/day instead of 34,700 ng/day.

“While we regret the error, this is a correction in one exposure example in the discussion section of the study,” lead author Megan Liu of Toxic-Free Future told us by email. “The example was not part of the core research objectives or methods of the study.”

Jones, who spent his career at Dow Chemical, told us the second corrigendum is “inadequate and still incorrect.”

“If the error is sufficiently large to only provide context, the statement in the Conclusions that brominated flame retardants ‘significantly contaminate products’ no longer can be supported and must be corrected or retracted following the reasoning presented in the second corrigendum,” Jones wrote in a letter to the editor published with the second correction.

Jones took to task some of the calculations and other estimates Liu and colleagues made, which the authors refute in a response to Jones’ letter, also published in Chemosphere this week.

The Elsevier journal was delisted from Clarivate’s Web of Science in December for failing to meet editorial quality criteria. Last December an Elsevier spokesperson told us the publisher’s ethics team was“conducting in-depth investigations” of “potential breaches of Chemosphere’s publishing policies.” The journal had published more than 60 expressions of concern in 2024 and has retracted 34 articles so far this year.

Part of delisting means Clarivate no longer indexes the journal’s papers or counts its citations. Google Scholar shows seven citations to Liu’s paper, and Dimensions lists four scholarly citations.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at team@retractionwatch.com.

Squid Game is back! The third and final season of the worldwide phenomenon has dropped, and I'm pleased to share that I'm back as host of Squid Game: The Official Podcast, from Netflix and Mash-Up Americans. Join me and co-host Kiera Please as we suit up and break down every shocking twist and betrayal, and the choices that will determine who, if anyone, makes it out alive. Alongside creators, cultural critics, and viral internet voices, we'll provide our own theories for how the season ends, and what Squid Game ultimately reveals about power, sacrifice, and the systems that shape us.

Spoiler alert! Make sure you watch Squid Game Season 3 Episode 5 before listening on.

In Season 3, Episode 5, "Circle, Triangle, Square," Kiera Please and I unpack the twisted politics of fairness, the final betrayal of the Os, and Player 456's decision to protect the baby -- even if it means risking everything. And Comedian Steven He ("EMOTIONAL DAMAGE!") joins the pod to break down Guard 011's revenge, Min-su's haunting farewell, and the flashback that finally reveals how the Front Man won his season. Plus, we put Steven in the hot seat for a ruthless game of "Who Wants to Be a Squid-ionaire?"

Read more »

Dear RW readers, can you spare $25?

The week at Retraction Watch featured:

- Springer Nature book on machine learning is full of made-up citations.

- Do men or women retract more often? A new study weighs in.

- Chinese basic research funding agency penalizes 25 researchers for misconduct.

- Remembering Mario Biagioli, who articulated how scholarly metrics lead to fraud.

Our list of retracted or withdrawn COVID-19 papers is up past 500. There are more than 60,000 retractions in The Retraction Watch Database — which is now part of Crossref. The Retraction Watch Hijacked Journal Checker now contains more than 300 titles. And have you seen our leaderboard of authors with the most retractions lately — or our list of top 10 most highly cited retracted papers? What about The Retraction Watch Mass Resignations List?

Here’s what was happening elsewhere (some of these items may be paywalled, metered access, or require free registration to read):

- “Journal plagued with problematic papers, likely from paper mills, pauses submissions.”

- The Trump administration may be walking back the announcement that it’s cutting contracts with Springer Nature, according to an update from Nature.

- Research papers from 14 institutions contained hidden prompts directing AI tools to give them good reviews.

- “RFK Jr. says medical journals are ‘corrupt.’” Former NEJM editors say they “know he’s wrong.”

- “Mass Leak Showed the Harvard Law Review Assessed Articles for DEI Values. Some Authors Say That’s Not a Problem.”

- “Amid White House claims of a research ‘replication crisis,’ scientists offer solutions” while some call it “overblown.”

- “Delving into LLM-assisted writing in biomedical publications.” Coverage in Nature & New York Times.

- “Indians are gaming US immigration to get Einstein visas meant for top scientists” using paper mills.

- “In a male-dominated field, my success became misconduct,” says “principal investigator of a multimillion-euro European project.”

- NIH-funded research is now open-access. But could cuts to funding “have a noticeable effect on publication volumes?”

- “Different Methods Of Identifying Preprint Matches Yield Diverging Estimates Of Rates Of Preprinting.”

- What incentives do companies need to publish research?

- “Exclusive: NIH still screens grants in process a judge ruled illegal.”

- “Journal Editors Do Not Need To Worry About Preventing Misinformation From Being Spread”: A debate from the European Association of Science Editors conference.

- “Why it’s important to know who did what in a research paper.”

- “Why too much biomedical research is often undeserving of the public’s trust.”

- Researcher who “published one article every three days” loses 16 papers.

- Researcher “advocates a shift toward ethical, responsible, and transparent use of LLMs in scholarly publication.”

- “Panel with AI experts to review appeal” of university student “penalised for academic misconduct” in Singapore.

- “Are AI Bots Knocking Digital Collections Offline? An Interview with Michael Weinberg.”

- “Attitudes to sanctions for serious research misconduct”: Survey of sleuths and integrity officers.

- “AI, peer review and the human activity of science: When researchers cede their scientific judgement to machines, we lose something important.”

- “Developing a Criteria Framework for Peer Review: A Critical Interpretive Synthesis.”

- “How Peer Review Became Science’s Most Dangerous Illusion.”

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at team@retractionwatch.com.

What's up, podcast listeners? We've got another episode of our podcast They Call Us Bruce. (Almost) each week, my good friend, writer/columnist Jeff Yang and I host an unfiltered conversation about what's happening in Asian America, with a strong focus on media, entertainment and popular culture.

In this episode, we welcome Dylan Park-Pettiford -- TV writer, combat veteran and author of the memoir Roadside: My Journey to Iraq and the Long Road Home. He talks about growing up as a Black/Korean American kid in Campbell, California; getting swept up in the post-9/11 patriotism that sent him to Iraq, where his days alternated between boredom and terror; losing his brother to gun violence; uncovering a part of his identity through family history; and the kinds of topics you might want to avoid writing about if your mom might eventually read your book.

Read more »

Squid Game is back! The third and final season of the worldwide phenomenon has dropped, and I'm pleased to share that I'm back as host of Squid Game: The Official Podcast, from Netflix and Mash-Up Americans. Join me and co-host Kiera Please as we suit up and break down every shocking twist and betrayal, and the choices that will determine who, if anyone, makes it out alive. Alongside creators, cultural critics, and viral internet voices, we'll provide our own theories for how the season ends, and what Squid Game ultimately reveals about power, sacrifice, and the systems that shape us.

Spoiler alert! Make sure you watch Squid Game Season 3 Episode 4 before listening on.

In Season 3, Episode 4, "222" we unpack how innocence gets weaponized when the baby is named the Game's newest player -- and explore what South Korea's plummeting birth rate says about why this baby holds so much weight. Then, activist and content creator Amber Whittington (aka "AmbersCloset") joins to break down the heartbreaking end to the Jump Rope game, the Front Man's shocking reveal, and faces off with Kiera in a game of "Poisoned Bottle" that’s equal parts delicious and disgusting. Also: we call my mom to get her latest Squid Game takes!

Read more »

Mario Biagioli, a distinguished professor of law and communication at the University of California, Los Angeles — and a pioneering thinker about how academic reward systems incentivize misconduct — passed away in May after a long illness. He was 69.

Among other intellectual interests, Biagioli wrote frequently about the (presumably) unintended consequences of using metrics such as citations to measure the quality and impact of published papers, and thereby the prestige of their authors and institutions.

“It is no longer enough for scientists to publish their work. The work must be seen to have an influential shelf life,” Biagioli wrote in Nature in 2016. “This drive for impact places the academic paper at the centre of a web of metrics — typically, where it is published and how many times it is cited — and a good score on these metrics becomes a goal that scientists and publishers are willing to cheat for.”

Such cheating takes the form of faking peer reviews, coercing citations, faking coauthors, or buying authorship on papers, among other tactics described in the 2020 book Gaming the Metrics: Misconduct and Manipulation in Academic Research, which Biagioli edited with Alexandra Lippman.

“Mario saw the increasing reliance of metrics within scholarship, and their gaming, not simply as a moral problem but rather as an intellectual problem,” said Lippman, whom Biagioli mentored in a postdoctoral fellowship. “Mario was interested in how the gaming of metrics fundamentally changed academic misconduct from epistemic crime – old fashioned fraud – to a bureaucratic one – the post-production manipulation of impact.”

Lippman and Biagioli organized a conference at the University of California, Davis, in 2016 on the topic, from which the book Gaming the Metrics followed. “To create a serious conversation about this new issue, Mario invited not only historians of science, computer scientists, anthropologists and other scholars but also misconduct watchdogs and other practitioners from the trenches to share their research, expertise and perspectives,” Lippman said.

That conference “can be considered the moment when the milieu of the new style science watchdogs, to which belongs Retraction Watch, was launched,” said Emmanuel Didier, a sociologist and research director at the National Centre for Scientific Research in France. “It was the first time everyone met the other,” said Didier, who participated in the meeting.

Biagioli “had high expectations for excellence, a strong sense of adventure, and a constant twinkle in his eye along with a biting sense of humor,” Lippman said. He was “an expansive thinker,” she said, and his intellectual legacy “is also expansive through his work not only on scholarly metrics and misconduct but also on scholarly credit, intellectual property, copyright, academic brands, and scientific authorship.”

Biagioli earned his Ph.D. in the history of science from the University of California, Berkeley in 1989. Before joining the UCLA faculty in 2019, he taught at many institutions, including Harvard University, Stanford, and UC Davis, where he founded the Center for Science and Innovation Studies. His books addressing the history of science include Galileo, Courtier, published in 1993.

“I learned something from every conversation I had with Mario, and everything of his I read,” said our Ivan Oransky. “His way of looking at the structure of academia and scholarly publishing was unique, bracing, and constructive.”

Biagioli’s idea that “the article has become more like a vector and recipient of citations than a medium for the communication of content” is “a guide to what research assessment has become,” Oransky said. “He is already missed.”

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at team@retractionwatch.com.

In its second batch of misconduct findings this year, the organization responsible for allocating basic research funding in China has called out 25 researchers for paper mill activity and plagiarism.

The National Natural Science Foundation of China, or NSFC, gives more than 20,000 grants annually in disciplines ranging from agriculture to cancer research. The NSFC publishes the reports periodically “in accordance with relevant regulations,” the first report, released in April, states. The organization awarded 31.9 billion yuan, or about US$4.5 billion, in project funds in 2023.

The NSFC published the results of its investigations on June 13. The reports listed 11 specific papers and 26 grant applications and approvals.

The misconduct findings were similar to those in the NSFC’s first first batch in April. Offenses included “buying and selling of experimental research data” and “plagiarism, forgery and tampering.” As a result, NSFC barred those researchers from applying for or participating in grants for three or five years, and, in some cases, required grant recipients to pay back funds they’d already received.

Seven of the studies on the list, coauthored by 14 of the sanctioned researchers, were retracted before the report was released.

An email to the NSFC asking whether the organization informed the journals about the misconduct findings bounced back, but correspondence with several of the journals suggests the NSFC did not contact them.

Two of the papers that haven’t been retracted came from Oncotarget, an embattled journal. Elena Kurenova, the scientific integrity editor for the publication, told us the articles were already under investigation before the NSFC findings, but the journal was “not aware of the current NSFC report.” Kurenova told us given the results of their investigation and the report, “the Editorial decision was made to retract these papers.”

Four of the papers listed in the report come from journals published by Dove Press, part of Taylor & Francis: two in Onco Targets and Therapy (and retracted in 2022 and 2023), one in Cancer Management and Research, which the journal retracted in 2021, and one in the International Journal of Nanomedicine.

The editor-in-chief for the International Journal of Nanomedicine, which has not retracted the paper included in the report, did not respond to our request for comment.

Mark Robinson, media relations manager from Taylor & Francis, told us the article from International Journal of Nanomedicine was “already under investigation” before the report was released. He also said NSFC didn’t contact the journals about their report.

Two researchers named in the report, Yao Yang and Jinjin Wang, of South China Agricultural University in Guangzhou, included a paper they wrote in their grant applications that was retracted in 2024. NSFC penalized them for “buying and selling papers” and “unauthorized marking of other people’s scientific fund projects,” among other offenses. Neither responded to our request for comment.

Another paper by Yang and Wang, published in Water, had those same offenses and had not been retracted when NSFC’s report was released. Jovana Mirkovic, journal relations specialist at MDPI, which publishes Water, told us in an email the journal would be “issuing a retraction notice for this article.” She did not respond to our follow-up email regarding whether the investigation began before our email or whether she was aware of the NSFC report.

He Juliang, who listed affiliations with Guangxi Medical University, had two of his projects revoked. The notice says the “allocated funds” were “recovered” from the researcher. Juliang did not respond to our request for comment.

Wen Zhong, who listed affiliations with Jiangxi University of Science and Technology in Ganzhou, used a retracted paper in the application form, progress report, and final report of a project, according to the NSFC. The report also says he committed “plagiarism, forgery and tampering, use of other people’s signatures without consent, and unauthorized marking of other people’s fund projects.” Zhong did not respond to our request for comment.

Ten of the researchers were sanctioned after they “plagiarized the contents of other people’s fund project applications,” the report states.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at team@retractionwatch.com.

Squid Game is back! The third and final season of the worldwide phenomenon has dropped, and I'm pleased to share that I'm back as host of Squid Game: The Official Podcast, from Netflix and Mash-Up Americans. Join me and co-host Kiera Please as we suit up and break down every shocking twist and betrayal, and the choices that will determine who, if anyone, makes it out alive. Alongside creators, cultural critics, and viral internet voices, we'll provide our own theories for how the season ends, and what Squid Game ultimately reveals about power, sacrifice, and the systems that shape us.

Spoiler alert! Make sure you watch Squid Game Season 3 Episode 3 before listening on.

In Season 3, Episode 3, "It's Not Your Fault," we react to one of the season's most devastating twists, the newborn baby's forced induction into the Game and Player 456's newfound purpose. Plus, we break down the backstory of our favorite creepy dolls: Young-hee and Chul-su and their role in Korean education. Then, special guest Philip Wang of Wong Fu Productions joins to talk about the show's evolving definition of family -- and what it means when even the heroes have blood on their hands. Plus, we face off in a morally impossible round of "The Lesser Evil" -- because sometimes, there are no right answers.

Read more »

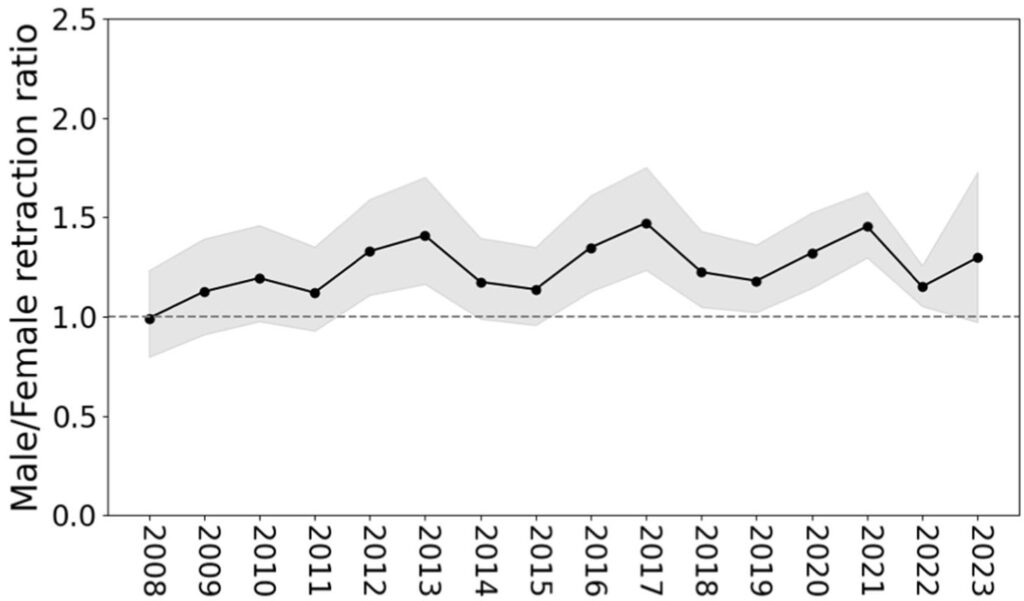

When you look at retracted papers, you find more men than women among the authors. But more papers are authored by men than women overall. A recent study comparing retraction rates, not just absolute numbers, among first and corresponding authors confirms that men retract disproportionally more papers than women.

The paper, published May 20 in the Journal of Informetrics, is the first large-scale study using the ratio of men’s and women’s retraction rates, said study coauthor Er-Te Zheng, a data scientist at The University of Sheffield. The researchers also analyzed gender differences in retractions across scientific disciplines and countries.

Zheng and his colleagues examined papers from a database of over 25 million articles published from 2008 to 2023, about 22,000 of which were retracted. They collected the reasons for retraction from the Retraction Watch Database, and used several software tools to infer each author’s gender based on name and affiliated country.

“The biggest limitation is gender inference,” Zheng said. The researchers couldn’t determine gender of the first authors of 47.1% of the retracted papers and 23.3% of the non-retracted papers. The software tools the authors used draw on historical Western-based name databases, which do not account for nonbinary authors or those from non-Western countries.

Whether looking at first authors or corresponding authors, men had an overall higher overall rate of retraction than did women, but the researchers found no difference when looking at papers retracted due to mistakes. However, men had higher rates of retraction for misconduct, especially plagiarism and authorship issues.

“The difficulty from all these studies, when we say that men are committing more misconduct than women, is what do we have to do?” said Evelyne Decullier, a methodologist at Hospices Civils de Lyon in France who examined gender differences in retractions within health sciences in a study published in 2021. “We need to understand what is behind that.”

Among the 10 countries with the most retracted articles, among first authors, men had a higher retraction rate than women in Iran, Pakistan, and the United States. Women had higher retraction rates in China and Italy, though the researchers noted that the data from China needs further validation, as over 80% of the authors with unidentified gender were affiliated with Chinese institutions.

Men had higher retraction rates in biomedical and health sciences, and life and earth sciences. These results align with prior studies, said Ana Catarina Pinho-Gomes, a public health consultant at University College London who conducted a similar 2023 study focusing on retractions within biomedical sciences. In contrast, Zheng and his colleagues found that women retracted papers at a higher rate in mathematics and computer science.

While the study was descriptive and cannot address the reason for this result, the authors have a hypothesis. “There may be some cultural and expectational differences in this field that women are historically underrepresented in,” Zheng said. “This may create some pressure or expectation for female researchers.”

In addition to pressures at the author level, “perhaps there is a bias in the evaluation process that leads to female authors having their work scrutinized more closely,” said Mariana Ribeiro, a postdoctoral researcher at Brazil’s National Cancer Institute who has examined gender differences in self retractions. (She is also a Sleuth in Residence at the Center for Scientific Integrity, the parent nonprofit of Retraction Watch). Alternatively, “we cannot disregard the possibility that women may be more reluctant to self-correct or to accept corrections to their work, fearing negative repercussions that could also be amplified by existing gender biases.”

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at team@retractionwatch.com.